Whitesboro, New York

Whitesboro, New York | |

|---|---|

Commercial buildings on Main Street in Whitesboro | |

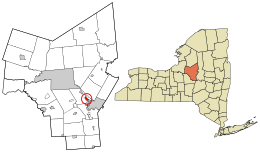

Location in Oneida County and the state of New York. | |

| Coordinates: 43°7′N 75°18′W / 43.117°N 75.300°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Oneida |

| Founded by | Hugh White |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.05 sq mi (2.72 km2) |

| • Land | 1.05 sq mi (2.72 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 423 ft (129 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 3,612 |

| • Density | 3,440.00/sq mi (1,328.72/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 13492 |

| Area code | 315 |

| FIPS code | 36-81710[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0971160[3] |

| Website | Official website |

Whitesboro is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 3,772 at the 2010 census. The village is named after Hugh White, an early settler.[4]

The Village of Whitesboro is inside the Town of Whitestown.

History

[edit]The village began to be settled in 1784, and was incorporated in 1813. An 1851 list gave the name Che-ga-quat-ka for Whitesboro in a language of the Iroquois people.[5]

The abolitionist Oneida Institute (1827–1843) was located in Whitesboro.

The older part of the village was bordered by the Erie Canal and the village's Main Street. When the canal was filled in the first half of the 20th century, Oriskany Boulevard was built over the filled-in canal. The streets that connect the two roads form the oldest part of the village.[citation needed]

The Whitestown Town Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[6] It currently serves as the village courthouse, while offices for the Town of Whitestown are housed in newer buildings outside of Whitesboro.[7]

Village seal controversy

[edit]

The Whitesboro seal, originating in the early 1900s, displays founder Hugh White wrestling an Oneida Native American.[8] The seal has been controversial because it has been interpreted as a settler choking the Native American; city officials contend it depicts a friendly wrestling match that White won, gaining the respect of the Oneida.[9] The 1970-2017 version of the seal was created after a lawsuit by a Native American group: the version used before the suit showed the settler's hands on the Native American's neck instead of his shoulders.[10] In 1999, Mayor John Malecki suggested a contest for a new seal, but received no submissions.[11]

The seal received attention in 2015 as part of national discussion about display of the Confederate flag.[12][11] In January 2016, the town cooperated with Comedy Central's The Daily Show to hold a non-binding vote for a new village seal. Many of the alternative seals were humorous, including one depicting the two men as luchadores and another depicting an arm wrestling contest. Village residents voted 157 to 55 to keep the seal as-is.[9] Afterwards, Mayor Patrick O'Connor was criticized for not disclosing Comedy Central's involvement.[13] The Daily Show's January 21 show covered the vote and the controversy around the seal. At the end of the segment, correspondent Jessica Williams announced that the mayor told her that the town would change the seal.[14] This was confirmed by a joint press release from Whitesboro and the Oneida Indian Nation the next day.[15]

An updated seal was adopted in the summer of 2017.[16] The new seal was created by a communication design student at PrattMWP in Utica, under direction of a professor there.[17] While the new seal depicts the same scene as the previous seal, it moves White's hands down to the Oneida chief's upper arms instead of near his neck, and neither man appears to be dominating the other.[18] Additionally, both men were given more realistic skin tones, and their attire was corrected for historical accuracy.[19]

Geography

[edit]Whitesboro is located at 43°7′N 75°18′W / 43.117°N 75.300°W (43.124, -75.296).[20] According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), all land.[21]

The Sauquoit Creek forms the boundary with Yorkville. Areas of Whitesboro near the creek suffer from periodic flooding.[22]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 964 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,370 | 42.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,663 | 21.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,958 | 17.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,375 | 21.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,038 | 27.9% | |

| 1930 | 3,375 | 11.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,532 | 4.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,902 | 10.5% | |

| 1960 | 4,784 | 22.6% | |

| 1970 | 4,805 | 0.4% | |

| 1980 | 4,460 | −7.2% | |

| 1990 | 4,195 | −5.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,943 | −6.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,772 | −4.3% | |

| 2020 | 3,612 | −4.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 3,943 people, 1,778 households, and 992 families residing in the village. The population density was 3,675.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,419.1/km2). There were 1,921 housing units at an average density of 1,790.6 per square mile (691.4/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.69% White, 0.53% African American, 0.03% Native American, 0.33% Asian, 0.53% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.47% of the population.

There were 1,778 households, out of which 27.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.9% were married couples living together, 15.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.2% were non-families. 39.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.7% had someone living alone who were 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 23.3% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 31.7% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 17.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 86.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.2 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $31,947, and the median income for a family was $42,741. Males had a median income of $29,408 versus $25,865 for females. The per capita income for the village was $17,386.

Notable people

[edit]- Sidney Breese, Illinois pioneer

- Calvert Coggeshall, painter

- Alexander L. Collins, politician

- Harriet Elizabeth Cook, a wife of Brigham Young, was born in Whitesboro in 1824.[24]

- Simon Newton Dexter, politician

- Robert Esche, former professional ice hockey goaltender, currently President of the Utica Comets

- John Frink, writer and executive producer for The Simpsons

- George Washington Gale, founder of the Oneida Institute of Science and Industry, later the Oneida Institute

- Thomas R. Gold, politician

- Beriah Green, president of the Oneida Institute

- John Grimes, Roman Catholic bishop

- Mark Lemke, former Major League baseball player with the Atlanta Braves

- William A. Moseley, former US Congressman

- Mark Mowers, former professional ice hockey winger

- Harry S. Patten, politician

- Charles Edward Pearce, congressman

- Fred Sisson, politician

- John T. Spriggs, politician

- Henry R. Storrs, lawyer

- Johnny Sullivan, wrestler

- William Whipple Warren, 19th-century historian of the Ojibwe and Minnesota Territory legislator, attended school at the Oneida Institute

- Philo White, former Wisconsin state senator, U.S. diplomat

References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Transactions of the Oneida Historical Society at Utica, 1881–1884 Archived May 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p.73 et seq. (1885)

- ^ Jones, Pomroy (1851). Annals and recollections of Oneida County. Rome, New York: Published by the author. p. 872.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Whitesboro Village Courts". Village of Whitesboro. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ Katz, Brigit. "New York Village Changes Controversial Seal Showing a White Settler Wrestling a Native American". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Santora, Marc (January 12, 2016). "Residents in Whitesboro, N.Y., vote to keep a much-criticized village emblem". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Potts, Courtney (January 4, 2009). "Whitesboro seal 'takes a little explaining'". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Whitesboro seal caught up in rebel-flag debate". Observer-Dispatch. July 17, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Connor, Jackson (July 7, 2015). "Mayor of Whitesboro, N.Y., Insists This Village Seal Is Not Racist". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Cleaver, Jolene (January 13, 2016). "Whitesboro mayor: Disclosing TV presence 'would have tainted the seriousness' of seal vote". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Wrestling with History in Whitesboro, NY". The Daily Show. January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Whitesboro, Oneidas to work together on new seal". Observer-Dispatch. January 22, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Krull, Melissa (September 25, 2017). "Whitesboro officially replaces controversial seal". Spectrum News 1 Central New York. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Koren, Cindiana (September 27, 2017). "Solving Racism – Whitesboro – UPDATE – meetinghouse.co". www.meetinghouse.co. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Maya Salam (September 27, 2017). "New York Village's Seal, Widely Criticized as Racist, Has Been Changed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Cleaver, Jolene (September 26, 2017). "After past uproar, Whitesboro has new village seal". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Search Results". www.census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Edward (March 4, 2022). "Whitestown project to ease Sauquoit Creek flooding avoids snags as it moves ahead". Utica Observer Dispatch. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Harriet Elizabeth Cook". Church History Biographical Database. August 5, 1910. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Whitesboro, New York at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Whitesboro, New York at Wikimedia Commons- Village of Whitesboro, NY

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).